Something for Everyone: The Story of God Bible Commentary

John Wimber wrote:

“The Bible is unlike any other book. It is a collection of incredible love letters from God, telling us about our relationship with him. Small wonder that we are called to be men and women of The Book, meditating on God’s Word and allowing it to transform our minds, hearts, souls, and actions.” (The Way In is the Way On)

From our beginning, the Vineyard has always had a high view and value for Scripture. We are committed to being people of Scripture and the Spirit, refusing to live in an “either/or” world because we embrace the “both/and.” Due to this commitment, the Society of Vineyard Scholars often receives questions related to the Bible and an often repeated question is related to Bible commentaries. Which ones are the best? Which can be trusted? Which can be understood? The questions abound.

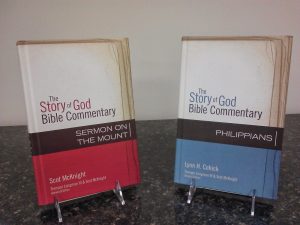

Recently Zondervan began publishing a new series called The Story of God Bible Commentary series (SGBC). According to the series’ website, the SGBC series “provides pastors, Sunday school teachers, small group leaders, and committed Bible students with a clear and compelling exposition of Scripture, setting each passage in context with the Bible’s narrative arc.” In this review, I’d like to first introduce you to the series and then take a brief look at two of the commentaries in SGBC: Scot McKnight’s The Sermon on the Mount and Lynn H. Cohick’s Philippians.

Meet the Story of God Bible Commentary

Based on the New International Version (NIV 2011) this commentary series boasts some of the best evangelical scholars of the day while representing a diverse theological spectrum. The Old Testament’s general editor is Tremper Longman III and the New Testament’s general editor is Scot McKnight. In addition, commentators include Christopher J. H. Wright (Exodus), Mark J. Boda (Isaiah), our very own Beth Stovell (Minor Prophets), Michael F. Bird, Mariam J. Kamell. and a host of other international men and women who are ethnically diverse and well suited for the task. Moreover, the editors make the bold statement that “this series has a wider diversity of authors than any commentary series in evangelical history.”

Based on the New International Version (NIV 2011) this commentary series boasts some of the best evangelical scholars of the day while representing a diverse theological spectrum. The Old Testament’s general editor is Tremper Longman III and the New Testament’s general editor is Scot McKnight. In addition, commentators include Christopher J. H. Wright (Exodus), Mark J. Boda (Isaiah), our very own Beth Stovell (Minor Prophets), Michael F. Bird, Mariam J. Kamell. and a host of other international men and women who are ethnically diverse and well suited for the task. Moreover, the editors make the bold statement that “this series has a wider diversity of authors than any commentary series in evangelical history.”

SGBC is unique in that it is an accessible series that is written for our current cultural landscape. As the editors note, “Culture shifts, but the Word of God remains.” So what does the Bible have to say to a shifting culture? How should we understand Scripture in a more diverse and global church? These are the types of questions that SGBC attempts to answer as well as provides the context for how the series structures its commentaries.

Each commentary is broken into three sections:

- Listen to the Story presents the Bible passage in the New International Version (NIV).

- Interpret the Story examines the passage for its essential message and meaning.

- Live the Story explores how we can live this text in the world today. It offers insightful reflections, illustrations, and practical suggestions for daily Christian life and practice.

In what follows, I want to look at two examples of the SGBC series: Scot McKnight’s Sermon on the Mount and Lynn H. Cohick’s Philippians.

McKnight’s Sermon on the Mount

Scot McKnight, New Testament scholar, professor, and popular blogger at Jesus Creed, introduces his commentary with the following:

“The Sermon on the Mount is the moral portrait of Jesus’ own people. Because this portraint doesn’t square with the church, this Sermon turns from instruction to indictment. To those ends — both instruction and indictment — this commentary has been written with the simple goal that God will use this book to lead us to become in real life the portrait Jesus sketched in the Sermon.” (p. 1)

McKnight goes on to lay out, in the “Introduction,” issues that interpreters face, such as how to account for church history’s “silencing” of the sermon, issues of moral theory and ethics, and authorship. This introduction is perfect for the SGBC’s purpose and target audience in that it doesn’t get bogged down with to many technical issues but certainly introduces readers to ideas that they may encounter when reading other commentaries on the Sermon on the Mount.

Following the series’ format, each pericope is included in the “Listen to the Story” section, which also includes intertextual references that the author finds important and serves to understand the context. Following the text in question, McKnight provides insights into how the text is to be understood and interpreted. In fact, in addition to the helpful insights that include textual, cultural, and other comments of importance, Sermon on the Mount includes for each passage a section called “Explain the Story.” Clearly the SGBC is concerned with providing helpful exegetical information to enable readers to make reasonable interpretive decisions. Finally, the “Interpret the Story” section is followed by a “Live the Story” focus which paints a picture of how the text is to be applied in today’s culture. This framework follows through McKnight’s SGBC contribution and is a great format for the target audience.

Since this is simply an introduction to the series, I’d like to comment on McKnight’s work on Matt. 7:15-23. McKnight writes that “anyone who has spent much time with judgment texts in the Bible knows that the Bible teaches that our final destiny is determined by works. We may be saved by faith, but we are judged by works. Every judgment scene in the Bible is a judgment by works” (p. 264, emphasis his).

McKnight’s concern for this passage is that it be read and allowed to shape the way that we understand salvation and discipleship. His comments are nothing peculiar to classic Protestant theology and certainly do not teach that Justification is gained through one’s work. Yet McKnight acknowledges that “the rhetoric of Jesus here emphasizes works; I will do the same” (p. 265).

In my mind, this section is where McKnight shines. Unwilling to neuter the words of Jesus and yet fully aware of and in agreement with Protestant soteriology (with clearly some nuances, as can be found in The King Jesus Gospel), McKnight does a splendid job of addressing the two sections of the text, the deceiver (7:15-20) and the deceived (7:21-23). However, the goldmine is in how McKnight challenges readers to “Live the Story.” The question is simple: who is this text addressed to? McKnight challenges readers, influenced by Mark Allan Powell, to acknowledge that they may read this text assuming themselves as correct. Thus, preachers will often assume they are in the place of Jesus and laypersons may identify themselves as either faithful or hypocrites. Yet McKnight challenges readers, especially those who serve as pastors or leaders, to start by placing themselves “under the word of Jesus and to ask if she or he might be the false prophet” (p. 269). The implications of McKnight’s comments and application are that “works tell the truth” about who Jesus’ disciples are.

Anyone interested in or passionate about discipleship, missional living, evangelism, or sanctification will likely love McKnight’s contribution to works on the Sermon on the Mount. While especially geared toward being accessible for non-scholars, I’d suggest that for scholars who are also disciples of Jesus, McKnight’s commentary will be personally helpful.

Cohick’s Philippians

Truth be told, Paul’s letter to the Philippians is one of my favorite epistles in the New Testament. My first expository sermon series was on Philippians and I read through most of O’Brien, Fee, Wright, Thielman, Bruce, Motyer, Martin and a host of other scholars. I consumed Witherington’s socio-rhetorical work and listened to every online lecture I could find on this epistle.

The bottom line is that I love Philippians, so I was very interested to read through Cohick’s commentary.

Lynn H. Cohick is a NT scholar at Wheaton and given that I really enjoyed her NCC contribution on Ephesians, I knew I would likely not be disappointed in her SGBC contribution. Following the series’ three easy-to-use sections, Cohick writes a very readable, insightful, and applicable commentary on one of Paul’s warmest epistles.

In my mind, Cohick demonstrates a profound understanding of the ancient world’s mileu as well as a serious appreciation for Pauline theology (and praxis). Yet her SGBC work is not bogged down with items that would likely be unappreciated by non-scholars. Rather, Cohick’s commentary is full of practical application. While readers will greatly appreciate her exegetical comments, she excels when providing how the text is to be lived out.

For example, after Cohick provides a significant amount (20 pages!) of well reasoned explanations on Phil. 2:6-11, her “Live the Story” section brings out why this passage is so important and how it can be applied. Beginning with a great story that illustrates her conviction that biblical exegesis and theology are not mutually exclusive endeavors but should be conversation partners, Cohick then demonstrates that the implications of the Christ hymn is toward a fully developed awareness that followers of Jesus are called to serve, not be served. Her examples are practical and serve preachers well in that they open the door for further reflection and creative application.

Conclusion

All in all, the SGBC series is fantastic and clearly delivers on its goals, both in regards to purpose and audience. I would highly recommend that pastors and Bible teachers pick up copies as they look for expository help since the series is so well balanced.

Finally, I’d like to note another important item that stood out to me as I read through McKnight and Cohick’s contributions. If the other contributions are similar to these two examples, students of the Bible will find the SBGC series helpful no matter where they are living. These do not strike me as being full of insights and practical applications that will only find place in North America or Eastern Europe. In fact, as I read through these two books, I kept asking myself if my friends in eastern Africa or Nepal or South America would find the sections on living the text out helpful. More often than not, I think they would.

Therefore, I want to introduce Zondervan’s new series, The Story of God Bible Commentary, as well as encourage you to pick up your copy today. And do keep your eyes open for our very own Beth M. Stovell’s two contributions in this series: Minor Prophets I and Minor Prophets II.

Tags: Bible Commentaries, Exegesis, Exposition, Expository Sermons, Homiletics, Recommended Commentaries, The Story of God Bible Commentary

Jon Stovell · July 26, 2014, 08:22 PM

I haven't read McKnight's Sermon on the Mount volume yet, but I can wholeheartedly concur that Cohick's Philippians is excellent. Since you mentioned her discussion of Phil 2:6–8, @Luke Geraty, I'll mention that I was very pleased with her handling of the relationship between the lines "he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave" and the lines "Coming to be in human likeness, and being found in human appearance". Specifically, she rightly argues that "Coming to be in human likeness" is not a synonymous parallel with "he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave." This is vitally important to realize for all sorts of theological and practical reasons in both Christology and theological anthropology. Cohick does an especially admirable job of highlight some of the chief problems for our understanding of what it means to be human that can arise from the prevalent misreading of this verse. That alone, frankly, is worth the price of the book.

Of course, EVERYONE will need to read Minor Prophets I and Minor Prophets II when they are released. I know on the basis of inside knowledge that is in absolutely no way biased whatsoever that those two volumes really are going to be absolutely fantastic.