A Review of Peter Enns’ New Book on Scripture!

A few weeks ago, I met a young man at Pascal’s Coffee for a chat. He told me he’d been in a bit of a crisis of faith and had some questions about the Bible. We sat down and he immediately produced a printed paper containing a list of ‘contradictions’ in the Bible as well as a copy of Evidence that Demands a Verdict. I smiled, knowing what’s next. I’ve had this conversation a few times before. His big question: given all of these contradictions, how could he trust the Bible? My response question: trust the Bible for what? We talked for an hour about what the Bible is for – how its not meant to be a history or science textbook and how holding it to that modernist standard involves bringing expectations to it that it was never meant to meet. We talked about genre and author intention and how the truths conveyed by a story don’t always depend upon the story’s historical accuracy. And we talked about the Bible – about its power to bring things out in us, about it being a place where God meets us and teaches us and changes us – and how none of that depends on whether or not the Bible is a perfect document, free from historical error or internal contradiction.

A few weeks ago, I met a young man at Pascal’s Coffee for a chat. He told me he’d been in a bit of a crisis of faith and had some questions about the Bible. We sat down and he immediately produced a printed paper containing a list of ‘contradictions’ in the Bible as well as a copy of Evidence that Demands a Verdict. I smiled, knowing what’s next. I’ve had this conversation a few times before. His big question: given all of these contradictions, how could he trust the Bible? My response question: trust the Bible for what? We talked for an hour about what the Bible is for – how its not meant to be a history or science textbook and how holding it to that modernist standard involves bringing expectations to it that it was never meant to meet. We talked about genre and author intention and how the truths conveyed by a story don’t always depend upon the story’s historical accuracy. And we talked about the Bible – about its power to bring things out in us, about it being a place where God meets us and teaches us and changes us – and how none of that depends on whether or not the Bible is a perfect document, free from historical error or internal contradiction.

As a professor at a large public university not far below the Bible belt, I encounter this fairly often. Many students come into college with a received faith, built like a house of cards that has yet to encounter a breeze. Then their first history or philosophy or biology class blows through them like a hurricane and it all comes crashing down. Often the foundation of this architecture is some strong version of the doctrine of inerrancy: the idea that the Bible is the perfectly accurate, contradiction-free, manual for all life’s ills written word-for-word by God himself (as dictated to his chosen authors).

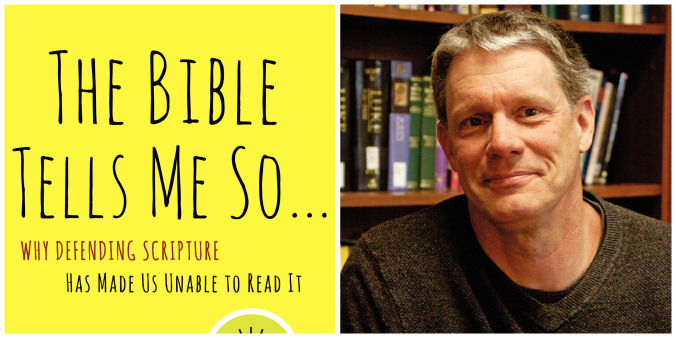

Peter Enns would like to destroy that foundation. Or, more accurately, he wants us to see that the Bible destroys it for us. In The Bible Tells Me So: Why Defending Scripture Has Made Us Unable to Read It (HarperOne), Enns invites readers to take an honest look at the Bible with all of its bumps, bruises, flaws and conflicts. God does bad stuff in the Bible, he tells us, and Biblical writers often disagree with one another, and oh, by the way, lots of the stuff in the Bible isn’t historically accurate and probably never happened at all.

If that’s a bit jarring, it’s because it’s meant to be. Enns doesn’t pull punches (“God never told the Israelites to kill the Canaanites. The Israelites believed that God told them to kill the Canaanites.”(p.54)), though every punch is delivered with a sly smirk and clever humor that’s refreshingly welcome to a topic like this. His stated aim, though, isn’t to undermine Biblical authority or its place as God’s Holy Word. It is, rather, the opposite. Enns is making the case that by bringing our inerrantist expectations of a perfect, conflict-free, historically-accurate, manual-for-life Bible to our reading of Scripture, we ask the Bible to conform to expectations it was never meant to meet and end up undermining much of its transformative power. In order to recapture that power, we have to learn to read scripture in ways that respects its ‘ancient voice’ and embrace the real challenges to faith that it raises. The Bible isn’t, according to Enns, God’s words written down, but rather an invitation to engage in a lifelong wrestling match with God. The Bible is “a forum for us to be stretched and to grow. These are the kinds of disciples God desires.” (p.22). The fact that the Bible doesn’t conform to our expectations of historical accuracy and consistency just reflects the Bible’s nature as a “model for our own spiritual journey. An inspired model, in fact” and “a book…that shows us what a life of faith looks like.”

Enns is certainly not the first to urge the faithful to consider the historical context of scripture and author’s intent when reading scripture. No scholar, however, is as relentless as Enns in taking this recognition to its logical conclusions. To say that historical context matters is also to say that the context of the authors matters, as well as their motivations for writing what they’ve written. And in all cases, Enns argues, those motivations for writing about the past are always strongly colored by concerns for the authors’ present. History is storytelling with a purpose:

Writing about the past was never simply about understanding the past for its own sake, but about shaping, modeling and creating the past to speak to the present. ‘Getting the past right’ wasn’t the driving issue. ‘Who are we now?’ was. (p. 232)

Enns shows how understanding this gives us a context for understanding many of the historical conflicts in the Bible – differences between, for example, the four Gospel accounts or between the dual accounts of Israel’s history found in Samuel-Kings and Chronicles. Talking about the latter, Enns notes that Samuel-Kings was written while Israel was in exile in Babylon and updated shortly after a return to the land. Its writers are trying to answer the question “How did we end up in Bablyonian exile when we thought God was with us? What did we do to deserve this?” The writers of Chronicles, on the other hand, wrote 200 years later after Israel had been back in Canaan for generations. Its central question is, “After all this time, are we still God’s people? Do we have a future?” It seeks to encourage Judah to keep the faith. This explains why, for instance, Samuel-Kings doesn’t hesitate to highlight the flaws and fallen leadership of David, Solomon, and every other king. Bad leadership is one of the main reasons Israel was divided and got carted off. In Chronicles, however, the flaws of these leaders are glossed over. They’re idealized, kingly blue-prints for a hopeful future.

This hermeneutic also applies to stories of the deep past found in Genesis, “not written to ‘talk about what happened back then’ [but] written to explain what is. The past is shaped to speak to the present.” (p. 112). Enns skillfully and playfully shows how the experience of Israel’s exile shapes everything from the creation accounts to the recurrent theme of younger brothers ruling over older brothers (written that way to explain, in Enns’ view, why Israel ‘the older brother’ kingdom did not survive exile while Judah, ‘the younger brother’ kingdom, did). Similarly for Israel’s divine mandate to the land of Canaan and justified destruction of the Canaanites, foreshadowed as early as the Flood and Noah’s cursing of Ham’s son Canaan. As Enns puts it, “It looks like whoever wrote this story has a bone to pick with the Canaanites.”

Enns carries the principle of the past serving the present over into the New Testament as well. In Chapter 6 of the book (‘No One Saw This Coming’), Enns argues that a key to understanding the NT writers is to realize that while they saw Jesus as deeply connected to Israel’s story, the language and experience of Israel’s story was not set up to handle Jesus – a totally unexpected crucified and resurrected Messiah. It therefore had to be reinterpreted in ways that few modern readers of Scripture would find comfortable. He notes that Jesus, for instance, radically reinterprets Psalm 110 to refer to himself, uses the story of the burning bush to make a claim about resurrection, relativizes the Sabbath, and at times makes the Torah stronger while at other times redirecting it completely. The Gospel writers act similarly – Matthew radically divorces a statement from Hosea about coming out of Egypt from its original reflective meaning and styles Jesus as a new Moses (in Enns’ terms, ‘Moses 2.0’), giving new laws from a new mount. Paul, Enns suggests, is perhaps the worst offender, in some ways sidelining the Torah altogether, making the mark of the new community not Torah-keeping, but Jesus-keeping. For the Torah-keepers of his day, Paul would have been seen as undermining Scripture. But Enns notes this was not a problem for Paul and other NT writers. “These writers did not fret about sticking to the biblical script. They couldn’t and they knew it. Scripture became more of a jumping-off point for talking about something the old language wasn’t set up to handle.” (p.199). As Enns points out, today many would call this ‘reading into the text,’ but in fact the NT writers’ creative reinterpretations of the Old Testament were completely at home in the Judaism of their day:

Debating the Bible, especially the Torah, and coming up with creative readings to address changing times was a mark of faithful Judaism…remaining faithful to the Bible in the here and now meant having to be flexible. The debates of the day were about how to be flexible and creative, not whether scripture was still binding.” (p 174)

This is, above all, the spirit of Biblical interpretation that Enns would like us to recapture – recognizing that reading Scripture is not an exercise in determining Truth, but an exercise in asking and answering questions that are relevant to our lives today. Who are we now? Why have things happened this way? How does my past inform my present and the other way around? Engaging with scripture this way frees us, Enns hopes, from the feelings of anxiety, disloyalty, unfaithfulness, and fear that often accompanies honest engagement with scripture. We can be free to lovingly disagree with one another’s interpretations because God-wrestlers have always disagreed. We can be free to disagree with stuff in the Bible because the Bible disagrees with itself (see Enns’ comparison of the themes of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes in chapter 4). And we can free the Bible from any modern requirement that it be historically accurate all the time.

This last one is a tough one for a lot of evangelicals – the ringing question of “How can we trust the Bible if it isn’t historically accurate?” immediately arises. But as Enns states, this question assumes that there is some necessary relationship between trust and historical accuracy when it comes to the Bible. If that relationship isn’t necessary, though – that is, if the Biblical writers were not especially worried about detailed historical accuracy as Enns claims, then “the passionate defense of the Bible as a ‘history book’…despite intentions, isn’t really an act of submission to God; it is making God submit to us.” (p.128).

We might wonder where all this leaves us. If we follow Enns in jettisoning the perfect, conflict-free, manual-for-life view of the Bible; if we accept that its writers had motivations rooted in their historical experiences for writing what they wrote and that not everything written as history in the Bible actually happened, can we still claim the Bible is the inspired Word of God, and what does that mean for us? Enns doesn’t have the aim here of presenting a theory of inspiration (see his popular 2005 book Inspiration and Incarnation for a fuller treatment of that topic), but he does provide some helpful thoughts. First, he points out that even the historical accounts in the Bible often have the shape of stories being told. God, it seems, like stories and likes to communicate using them. Second, God seems to have a principle of “letting his children tell his stories” for him in language they understand and in ways that make sense to them. This mirrors, it seems, God’s practice of relating to his people in linguistic and cultural ways that make sense to them as well.

For Enns, then, the Bible is a thoroughly human book, written by particular human authors in particular contexts and with particular motivations. Yet it is divine. How so? Because, as Enns says, “people just keep right along meeting God there.” (p. 236). This should not be too disquieting for Christians. After all, we believe that God himself, while fully divine, became a thoroughly human person who used human language and had human emotions. Enns is simply suggesting that we apply the same understanding to God’s Word that we apply to God’s “final Word” Jesus. For Enns, this puts the Bible in its proper place in our life of faith. “The Bible,” he writes “doesn’t say Look at me! It says, Look through me. The Bible, if we are paying attention, decenters itself….[it] is the church’s nonnegotiable partner, but it is not God’s final word: Jesus is.” Though not the intention, a strong, literalist, inerrantist view of the Bible often pits a ‘fully divine’ nature of Scripture against Jesus’ incarnational nature, letting Scripture win out.

One final note: Enns’ book is not an academic tome. There are no footnotes and few scripture references (these are compiled in an appendix that’s informative, but not very helpful). Plus, Enns is an easy to read, hilarious writer (rare traits among biblical scholars), making the book thoroughly accessible to anyone ready to engage in examining the question of how we are to read the Bible. The importance of the style of the book cannot, I think, be underestimated. There are few (if any) books on this topic that can engage readers in such a difficult conversation in such an entertaining and light-spirited way. This had me not only enjoying the book, but also thankful for it. I’ve had that conversation at the coffee shop about whether the Bible is trustworthy many times with many students. But now I have a new way to end it that I didn’t have before: “There’s a book I think you should read….”

About the author

Brent Henderson is an Associate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Florida. He attends and serves at the Vineyard of Gainesville.

Tags: book review, Peter Enns, review, Society of Vineyard Scholars, The Bible Tells Me So

John West · December 15, 2014, 06:00 PM

Thanks for the review Brent! I haven't read this book, but have read much of Enns other stuff, and also find him funny and thought provoking. The awkward part is that if Enns is even partially correct (and I suspect he is), then the vineyard statement of faith regarding the Bible is a little problematic: "the Bible is without error in the original manuscripts." And of course the problem is compounded by the fact the original manuscripts do not exist other than in the abstract.... Would love it if our statement of Faith moved in this direction: “The Bible,” he writes “doesn’t say Look at me! It says, Look through me. The Bible, if we are paying attention, decenters itself….[it] is the church’s nonnegotiable partner, but it is not God’s final word: Jesus is.” - To that I can say an unqualified Amen!